The Venture Capital Industry is Changing | Fintech Inside #95

How leading venture capital firms are abandoning traditional fund structures to become multi-billion dollar financial platforms and what it means for founders

Hi Insiders, I’m Osborne, an investor in early stage startups.

Welcome to the 95th edition of Fintech Inside. Fintech Inside is the front page of Fintech in emerging markets.

We talk about financial services a lot around here - that's what you're here for. But there's one sector in financial services I've never covered: the one I actually work in. Venture capital. And honestly, we're living through the most dramatic transformation this industry has ever seen.

I love studying the history of VC. The traditional model was beautifully simple: raise a fund, invest in startups, hopefully exit within ~10 years, return capital to investors. Rinse and repeat. But that’s slowly changing over the past few years.

Top VCs today aren't just early-stage investors anymore. They're becoming multi-faceted investment platforms capable of supporting companies with equity, debt, or whatever instrument makes sense, from inception through IPO and beyond. One is even building its own GPU infra!

As someone working in this space daily, I wanted to break down what's happening and why it matters - especially for founders navigating this new landscape.

Thank you for supporting me and sticking around. Enjoy another great week in fintech!

Considering angel investing? I get a bunch of fintech founders reaching out to me for investors. I’d be happy to put you in touch. I’m at os@osborne.vc

🤔 One Big Thought

The Great VC Reinvention: Why Traditional Funds Are Becoming Financial Platforms

We talk a lot about fintech around here. But today, we're covering the industry that funds it all: venture capital. And right now, the VC world is undergoing the most historic transformation since its inception. The old playbook—raise a fund, invest in startups, exit in 10 years, repeat—is being torn up by the very firms that perfected it. This is especially true for the larger venture funds.

Venture capital is no longer a cottage industry. Venture funds today are seemingly flexible, diversified investment platforms capable of supporting companies with equity, debt or other instruments, from inception through IPO and beyond. It has evolved from a niche, artisanal craft into a high-finance business.

The sector has grown from $53bn in global investment during the 2008 crisis to a record $640+bn in 2021, representing a fundamental shift in how innovation capital is deployed worldwide. And the top firms are reinventing themselves to deploy this capital at an unprecedented scale.

Why the shift? Part of the reason is scale and opportunity. The tech industry now supports companies that stay private longer and require larger capital infusions. Meanwhile, novel asset classes (like crypto or secondary shares) and founder needs (like liquidity and wealth management) have opened avenues for VCs to provide more than just equity funding.

The transformation addresses critical limitations of traditional VC structures: forced exits based on fund timelines rather than company performance, inability to maintain board relationships post-IPO, and exclusion of individual investors from private markets.

If you speak to active investors in financial assets, they'll tell you that each of their strategies have a ceiling on the total capital they can deploy for a particular strategy. For example, a long short strategy may have an upper limit of ~$50M, a quant strategy may have a ceiling of $100M, a mutual fund scheme could deploy maybe $150-200M etc. etc. Those aren't real numbers, but should give you a sense of what I mean by the ceiling.

This ceiling depends on depth in the market, risk-reward ratio and much more. the traditional model of VC, seems to have reached that ceiling and it now has to evolve or face the risk of being irrelevant. I think that ceiling gets breached for a fund size of $300-500M and total AuM of $2-3bn. Market depth matters too and some markets might not be able to absorb more capital.

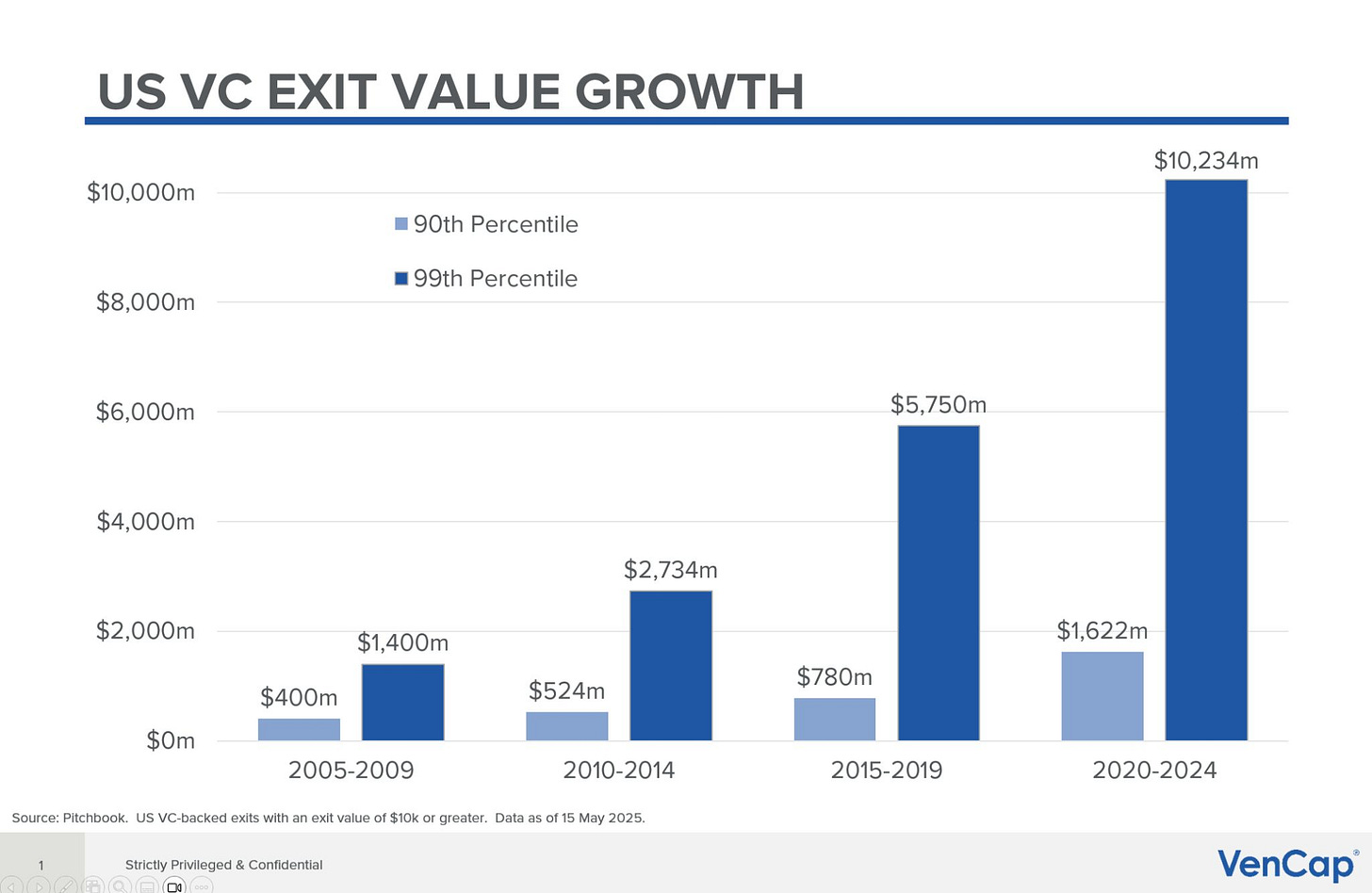

20 years ago, a 99th percentile outcome in VC meant, a $1bn valuation. Today, 99th percentile outcome is a $10bn exit valuation. Further, capital requirements of companies has grown. Lastly, LP's have more capital than ever to deploy. All of this warrants a business model shift for the venture capital industry.

The result is an industry in flux... finding itself.

As a student of this industry, I wanted to highlight the strategies/structures employed by some of these funds as they usher us into the future. To me, these structures are fascinating, interesting and thought-provoking. Let's dive in.

(Standard disclaimer applies - I'm not an expert on this topic, and my analyses are based on publicly available information.)

a16z's switch to a Registered Investment Advisor

Andreessen Horowitz (a16z) was the first among venture funds (to my knowledge) to transform its business model by becoming a Registered Investment Advisor (RIA) in 2019. This wasn't just a legal tweak; it was a strategic overhaul that unlocked immense flexibility for the $45bn+ firm.

How it works:

The structure is nothing fancy - the license to operate switches from a fund to a registered investment advisor.

Seems like, a16z will continue to raise capital into dedicated funds for specific themes like biotech and crypto.

Pros

Flexibility in assets held: the biggest benefit of an RIA is the ability to trade in private equity, crypto tokens, public equity, secondary markets and other alternative assets

Flexibility in holding tenor: the RIA is not time bound in its trades and can buy or sell as needed. a VC fund had a fixed timeline of 10+2 years.

Can still have dedicated fund structures: Specialised fund operations span multiple sectors with the 2024 fundraise of $7.2bn across Growth Fund ($3.75bn), Infrastructure Fund ($1.25bn), Apps Fund ($1bn), Games Fund ($600M), and American Dynamism Fund ($600M). Each fund operates with dedicated investment teams while leveraging shared platform services across all portfolio companies.

Portfolio optimisations: a16z can structure its investments more tax-efficiently across different asset classes. It can also potentially win investment opportunities in securities, asset classes or jurisdictions that other funds cannot.

Cons

High compliance costs: Reportedly, this structure comes with ~8x higher costs.

Potential operational drag: Employees have to go through background checks and register their investment holdings. They’ll also be more restricted in what they can trade individually and how they talk about financial performance.

Conflicts of interest: When you're investing across public/private/crypto simultaneously, whose interests come first?

Mission drift risk: Are they still great at finding the next Google, or are they just becoming a generic asset manager?

The interesting thing is that a16z launched The Oxygen infrastructure platform. It's a major competitive differentiator, providing AI startups access to over 20,000 Nvidia H100 GPUs through hundreds of millions in hardware investment. The program offers below-market pricing, flexible short-term access, and equity-based arrangements, enabling startups to compete with Big Tech on AI model development without $10M+ GPU commitments. This sort of program can only be built by a firm with massive AuM. Imagine any other fund building their own AWS!

Other developments include fundraising for a $20bn AI mega fund targeting growth-stage AI investments, launch of the a16z Perennial wealth management division with $822 million AUM, and active advocacy for modernised SEC crypto custody rules.

Sequoia's evergreen fund

Sequoia Capital's "The Sequoia Fund" seems to be the most radical departure from traditional VC structures. It announced it was "breaking with tradition, abandoning the traditional fund structure" with set 10-year cycles. Instead, Sequoia created a "singular, permanent structure" called The Sequoia Fund – essentially an evergreen fund that can hold investments indefinitely. That fund has grown to $20bn in assets as of 2024.

How it works:

Sequoia also became a Registered Investment Advisor (RIA) where one master fund serves as the sole LP for multiple sub-funds (seed, venture, growth, crypto).

When portfolio companies go public, shares flow into the master fund instead of being distributed to LPs, enabling indefinite holding periods and continued board participation.

Fee structures differentiate between sub-funds and the master fund. Sub-funds maintain Sequoia's premium 2% management fees and 30% carried interest, while The Sequoia Fund charges less than 1% management fees with performance fees tied to very high hurdle rates. This creates a hybrid model where traditional VC economics apply to private investments while public holdings operate under lower-cost structure.

LPs get to choose redemptions in semi-annual windows. LPs maintain accounts with The Sequoia Fund and can request allocations to specific sub-funds, providing some control over investment strategy mix.

Pros:

Simpler product for limited partners: LPs benefit from simplified public equity management and potential for higher long-term returns through extended holding periods, with Sequoia's internal analysis showing $8+bn in additional returns from holding shares just 12 months longer over the past 15 years.

Redemption flexibility for LPs: LPs can choose to stay invested or redeem semi-annually.

Longer partnership with founders: Portfolio companies benefit from continued strategic support post-IPO and reduced pressure for premature exits, while Sequoia gains permanent capital base eliminating fundraising cycles.

Not limited by fund or market cycles: With the Sequoia Fund, it can immediately redeploy gains instead of waiting 2-3 years to raise the next fund. With this, Sequoia can support portfolio companies through multiple economic cycles.

Cons:

Structure works for funds with a large public market exposure: Sequoia's portfolio companies have an aggregate 20% market cap of the NASDAQ! Sequoia has $85bn in total AUM, and $20Bn in the evergreen fund - that's 1/4th in publics. This is liquid holding that Sequoia could use to manage redemptions. Most other funds might not have that much access to the public markets.

"Bank runs": In a very remote chance where majority LPs want to redeem/exit their investment, Sequoia may have to dip too far into its public market pools which could cause a strain on the rest of the private market pools as well.

General Catalyst's multi-product strategy

General Catalyst has evolved into a comprehensive "investment and transformation company" through two major initiatives: GC Wealth - a wealth management platform; and the Customer Value Fund - a revenue-based financing model. With $32bn in total assets under management, these diversification efforts represent Hemant Taneja's "Beyond Venture" strategy to create multiple revenue streams while deepening ecosystem relationships.

Strategy:

Transformation company with capital: Nothing in its core funds structure seems to have changed, but GC is rethinking what being a venture capital firm is. Launching wealth management, revenue based finance and doing buyout deals (operational companies) is not very VC-like. But GC doesn't seem to care and I like that.

Wealth management: GC Wealth launched in 2024 with $2.3bn in AuM and 20+ employees. GC Wealth is led by Dave Breslin, former First Republic Private Wealth head who previously grew AUM from $60bn to $290bn. The platform targets founders, entrepreneurs, and high-potential individuals within GC's "Famiglia" community, providing personalised wealth management with access to private investment opportunities including GC funds. The wealth management model is intended to create powerful integration synergies with traditional VC operations. GC Wealth introduced ~40 new founders to GC's venture ecosystem, with some receiving funding, while GC's venture portfolio provides wealth management clients. The platform allocated $25M of client assets to GC's $8bn Fund XII.

Revenue based finance: The Customer Value Fund operates through revenue-based financing mechanics, providing non-dilutive capital secured by company recurring revenue streams. The most recent major investments include Grammarly ($1bn, the largest CVF investment) and FINOM (€92.3M). The structure allows companies to fund sales and marketing costs while paying back a capped percentage of revenue generated from funded customer acquisition activities.

Multiple revenue streams: Fee structures across the diversified platform create multiple revenue streams: traditional wealth management fees (likely 1-2% AUM), revenue-based returns from CVF capped at fixed percentages of customer acquisition outcomes, and standard VC fees of 2% management and 20% carried interest on $32+bn AUM. This diversification reduces cyclical dependence on traditional VC fundraising and exits.

Pros:

Suite of products to offer: GC now has a whole suite of products to offer founders, LPs and the ecosystem. It's not bound by just VC equity partnerships. It could easily offer revenue based finance to a startup where it's not an equity investor. Similar strategy for other products too.

Strategic positioning advantages include first-mover advantage in integrated wealth management among major VCs.

Powerful network effects through the GC Famiglia community

Unique end-to-end entrepreneur lifecycle support from startup funding to personal wealth preservation

Cons:

The approach risks focus dilution across multiple business lines and potential conflicts between VC and wealth management activities.

Fiduciary conflicts: Given there are so many fiduciary responsibilities, could there be any conflicts of interest? How do you serve someone's personal wealth interests when it could conflict with your portfolio company interests?

Coatue's CTEK Fund to democratise access

Coatue's CTEK Fund structure is the most interesting structure in my opinion - largely because I've not seen anything like it before. Claude tells me there are some specialised funds in US that use a similar structure though. With Sequoia, a16z and General Catalyst, the whole fund was restructured, but in Coatue's case, the main fund is the same, it's just that they've launched a new vehicle which gives them the flexibilities that the other mentioned funds enjoy.

Strategy:

This Coatue CTEK fund is a significant democratisation of institutional-quality technology investing, targeting qualified individual investors through an innovative tender offer fund structure. With $1bn in initial anchor capital from Jeff Bezos and Michael Dell's family offices, the fund reduces minimum investments from typical $5M Coatue requirements to $50,000 for broader accessibility.

The fund structure operates as a statutory trust registered as a non-diversified, closed-end management investment company. Three share classes (S, D, and I) offer different fee structures and minimum investments, with Class I requiring $1M minimums while Classes S and D require only $50,000. The product is being distributed via UBS US Wealth Management.

Investment strategy focuses on 80% minimum allocation to technology and innovation companies across AI, enterprise software, next-gen infrastructure, fintech, and climate technology.

Liquidity mechanisms differentiate CTEK from traditional private funds through quarterly redemptions up to 5% of net assets, monthly purchase opportunities, and NAV-based pricing. This structure provides enhanced liquidity compared to traditional 10-12 year lockups while maintaining exposure to private market returns.

Fee structures include 1.25% annual management fees and 12.5% performance fees above a 5% annual hurdle rate with high water mark protection. Distribution fees vary by share class from 0% (Class I) to 0.85% (Class S).

Pros:

This structure allows Coatue to deploy capital across early to growth to public markets and across sectors. In some ways, this will operate like The Sequoia Fund.

Massive TAM: Helps Coatue move from institutional-only to retail limited partners and potentially opens up trillions in AuM opportunity.

Cons:

Retail expectation mismatch: Individual investors may expect mutual fund-like liquidity in private markets. Individual investors also may not understand the risk that comes with investing in instruments like this.

Regulatory scrutiny: Retail investor protection rules are much stricter.

Operational nightmare: Managing thousands of $50K investors vs. a few $50M institutions is completely different

Competitive dynamics

The venture capital industry is maturing and morphing. The lines between venture capital, growth equity, private equity, and asset management are increasingly blurred.

The emergence of these innovative fund structures reflects broader industry trends toward permanent capital, enhanced liquidity, and democratized access. PitchBook projects evergreen funds will grow to approximately $500bn by 2029, with institutional evergreen funds increasing from $130bn to $300bn, representing fundamental shifts in how private capital operates.

Competitive advantages for innovative structures include continuous fundraising eliminating discrete cycles, flexible exit timing without forced asset sales, expanded investor bases accessing high-net-worth individuals and retail channels, and operational efficiency through single evergreen structures versus multiple sequential funds.

However, operational complexity requires sophisticated infrastructure with advanced technology stacks, dedicated personnel, third-party partnerships, and risk management systems.

Early trends and limited track record data suggests comparable risk-adjusted returns to traditional structures, though most evergreen funds lack long-term performance history.

Risk factors include higher operational costs (estimated 2-3x traditional fund administration), regulatory complexity across jurisdictions, and market concentration among larger GPs with operational capabilities.

Performance measurement challenges emerge from NAV dependency, benchmark comparison difficulties, and time horizon differences requiring new evaluation methodologies.

For founders, the mega-fund era might mean an even greater focus on later-stage or large fund raise requirements, “sure bet” companies (to deploy those billions), potentially making it harder for smaller startups to get attention. There’s also the question of returns: can venture funds manage $20B and still deliver venture-like performance? Or does VC inevitably become more conservative as it scales up? These are debates now playing out in real time.

What seems clear is that venture capital is no longer a cottage industry. It’s becoming a high-finance business, complete with complex structures and broad offerings. The classic model of a VC firm solely raising a $200M fund to invest in Series A rounds is being upended by firms like Sequoia, GC, Lightspeed, and a16z leading the charge in redefining what a venture firm can be. As more firms follow suit, the ecosystem will likely become more founder-centric and competitive – and perhaps more resilient, with diverse ways to weather market cycles.

Venture’s Ongoing Metamorphosis

These changes are opinionated bets on how venture firms can remain at the cutting edge. It’s an analytical response to a shifting market: adapt structure and strategy to capture more value and provide more value, or risk irrelevance. For general tech and finance observers, this evolution is fascinating (and a bit reminiscent of how investment banks or private equity firms diversified in the past). For entrepreneurs and LPs, it means more options – and also more factors to consider when picking a VC partner.

It’s also a statement about the maturing of the VC industry: top firms like a16z are now capable of absorbing PE-like sums of money. If the venture asset class used to be boutique, it’s increasingly looking institutional in scale. As Reuters noted, if Andreessen Horowitz pulls off $20B, it would be surpassed in size only by SoftBank’s vehicles, and it highlights ongoing debate about “how scalable” venture capital is while maintaining strong returns.

One thing is certain: venture capital’s metamorphosis is underway, and it’s making the industry more dynamic than ever. Don’t be surprised if tomorrow’s top “venture” firm looks as much like a multifaceted Wall Street financial institution as it does an old-school Sand Hill Road partnership. The business of funding innovation is innovating itself – and we’re seeing the first glimpses of what the VC firm of the future might look like.

1-min Anonymous Feedback: Your feedback helps me improve this newsletter. Click UPVOTE 👍🏽 or DOWNVOTE 👎🏽

🎵 Song on loop

Fintech updates can get boring, so here's an earworm: God Went Crazy by Teddy Swims (Youtube / Spotify). Smooth listening.

✨ Call outs

Rahul Sanghi of the Tiger Feathers published his latest and greatest post chronicling the company behind institutions like Bombay Canteen, O Pedro, Papas and more. I haven’t finished the piece yet (classic Rahul), but it’s a beautiful read so far (also classic Rahul). And I’d recommend you read it too.

If you’re an RHCP fan, you’d appreciate this one. Have you heard the song Can’t Stop? That intro riff sounds so simple and inane, right? This video takes you through the details of that simple riff explaining how complicated it really is and why even expert guitarists find it tough to replicate. The genius that is John Frusciante!

👋🏾 That's all Folks

If you’ve made it this far - thanks! As always, you can always reach me at os@osborne.vc. I’d genuinely appreciate any and all feedback. If you liked what you read, please consider sharing or subscribing.

1-min Anonymous Feedback: Your feedback helps me improve this newsletter. Click UPVOTE 👍🏽 or DOWNVOTE 👎🏽

See you in the next edition.